An Interview with Lisa J. Nutter, Principal, Sidecar Social Finance

For more about the Black & Bold: Perspectives on Leadership series, click here.

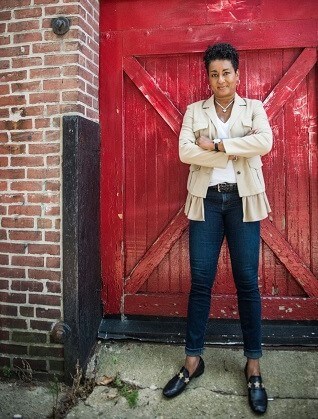

Lisa J. Nutter, Principal, Sidecar Social Finance

Authentic. Curious. Undercover radical.

Lisa J. Nutter lays bare the intricacies of financing scale and the challenges inherent within funding organizations equitably in the social sector. She asks, “How do we create a more flexible, innovative framework for how money is deployed and how do we look at problems to actually target the right resources at the right time?”

Tell me about your current role?

With two other colleagues, I’m a principal at Sidecar Social Finance. My transition to this role wasn’t a direct ride, as this is my encore career. I’m 54 years old, so I can talk about encore careers. (Laughter.)

In this role, I focus on how money flows to communities and organizations working in communities to support change in a meaningful way. In terms of my interests, I look at how investors and philanthropists are financing and helping to scale solutions to complex social issues and how that money facilitates solving problems. (Lisa Nutter pictured at right and below.)

I want to address the issue of building organizational capacity and individual wealth on the ground in communities in which some of these efforts are happening. There are also issues of equity – how money does and doesn’t flow to some change agents and in some communities. And, social entrepreneurs and the nonprofit sector don’t have the right capital to do the work needed. I’m not sure how we get work done without the right capital supporting the work at the right time – whether it’s traditional philanthropy or investment capital. The work with my colleagues at Sidecar allows me to take this in any direction I want and is a great opportunity to get underneath some obscure issues that folks don’t think about. We go straight to programming and don’t think about what’s under the hood as much. How do we finance this work? How do we put the right information in front of investors so they are allocating money to the right supports?

Is there a current example from your work you can share?

Sure, but I have to offer a bit of background. A current project that I created and am leading is called Financing Social Impact Innovation and Transformation at Scale or Financing Scale for short. I was so angry when I left Philadelphia Academies, Inc., so this started as a therapy project for me. I worked at Philadelphia Academies for thirteen years and ran it for twelve. We partnered with the School District of Philadelphia to scale an evidence-based youth development and high school transformation model. The work checked all the boxes: randomized control design research and a longitudinal study which determined that the model worked, and enough energy and capacity on the ground to execute even though the larger education system wasn’t always rowing in the same direction we were. In the third year of scaling the model, we were unable to maintain the level of funding needed to move to the next stage. It was more about the type of money we were working with than the amount; we had inflexible funding that was largely program-focused. No real room for innovation or learning. Ultimately, there were too many people with money deciding they wanted one thing from Column A and one thing from Column B which really affects how you operate. I call it the menu effect. You can’t cover all the organizational expenses working with fragmented and inflexible funding, nor can you focus on a long-term strategy.

The Financing Scale project lived in my head for a while. By design, it is focused on understanding the cross-sector perspective from people on the ground who are raising and managing funds and working through the challenges that come with venture capital, impact investing and traditional philanthropy. Financing Scale participants – the people collaborating with me on this journey – are bankers, venture capitalists, impact investment fund managers, technology entrepreneurs, academics, non-profit leaders, and folks leading in philanthropy. Their feedback really resonated with me. Their insights validated that I was not crazy: there is something wrong with the way money is, or I should say is not, designed around complex social problems and a general problem with how capital is thought about and distributed when it comes to the social sector.

In the next phase of the project, we’re piloting workable and doable ideas and solutions designed to improve how we finance scale – ideas that emerged from our conversations – in targeted communities. Those ideas have fallen into four big buckets: right capital, right time which is about capital design, fit and responsiveness; capital flow which is focused on financial inclusion and the equitable distribution of capital; ecosystem lens and framing which makes us engage communities differently, work from the bottom up and develop contextualized strategies; and, making sure that we’re evaluating what matters by starting with more honest conversations about reasonable outcomes, impact and timelines. This project emerged from obscure research and simply talking with folks to developing plans to actualize some of the solutions that we have identified as critical issues for the field.

For example, the issue of not having the right capital at the right time has real implications for our ability to change lives and communities. In the social sector, whether we are coming from for profits or non-profits, most of us are not working with the right capital to scale what we are doing. Many people use whatever grant program money is available and there are often unrealistic timelines attached to that money. How do we create a more flexible, innovative framework for how money is deployed and how we look at problems to actually target the right resources at the right time?

Another big issue is capital flow: who gets money, makes money, and where is the money going. On the who part, we know that communities and people of color have trouble accessing capital. At the same time, when capital is invested in communities and investors make money those communities are not building wealth in the process. It is as if communities and people living in them should just be happy that the investment is happening. There’s also a geographic slant to this. Communities in “fly over” states are also not getting investments. So, there are geographic disparities as well as disparities in race, class, and gender and these things are all connected. If we are trying to solve problems in these communities then we need to really invest in them and be inclusive in our approach.

Linked to this is the fact that there’s a broader ecosystem or landscape in the backdrop of every investment choice and investors need to know deeply about the ecosystem capacity in communities they’re funding. Often investors and philanthropy end up funding a lot of “points of light” and sexy ideas without a good place-based strategy and understanding how these things connect, or not, to other investments, policy choices, and institutional strengths. The community should be engaged to develop these strategies.

When it comes to impact, the emphasis on evaluation and standardization is very important to investors, but there isn’t honest dialogue about what’s really possible. Investors don’t know enough about the work to make a judgment and sometimes the change agent themselves doesn’t know enough or isn’t always comfortable being honest; it’s a dishonest dance where we never really learn what should be measured, when, and why. Never learning from the conversation as equals at a table holds the social sector back. We often sit in a compliance environment where we can’t talk about our mistakes. Name an industry that succeeds without being honest about its mistakes?

I know I keep saying this, but I’m 54 which means that I’m two years from outliving my mother. I’m not trying to solve problems for one person at a time. We’re out of time and this issue around scale has been a huge body of work for me. I’m enjoying the flexibility that I have in my partnership with Sidecar to focus on this project, be a thought leader and doer and I am in a space that has become not just therapeutic, but I feel like I am still in the battle.

What are some of your career highlights?

There’s one category: every time I run into a young person that my former organization, Philadelphia Academies, supported and hear from them about what they are doing now. Philadelphia is a big city but relationally very small, so you see people you know and are related to downtown all the time. I can’t point to any one moment, but every time I run into a young person and get a hug and thanks for how we supported them is like getting a bouquet. I remember how they were in high school and can see how far they have come. They attribute where they are to Philadelphia Academies’ work and there is nothing better than that.

If there was a headline for your leadership journey throughout your career, what would it be?

I think it’s that I tried to bring a vision that was way bigger than what was in front of me if that makes any sense. When I was at Philadelphia Academies, I had the opportunity to raise a significant amount of money for my community so I did. I guess I could have decided to just take care of Philadelphia Academies, but it was important to me for us to grow as a system – an ecosystem of organizations – focused on young people. It’s necessary to always keep the vision well beyond what is in front of you. That’s what vision is. This concept is reinforced for me in competitive track cycling where I compete at the master’s level riding forty miles an hour on a bike with no brakes. I’ve been trained to look straight ahead and down the track as I sprint. If you only look where you currently are, then you won’t keep your eyes on where you are going and actually can’t ride as straight or as fast.

What are your favorite types of challenges?

I like messy and the messier the better. I spent most of my career in the community development field. I think about what constitutes a community where social, cultural, educational, economic issues all come together in one place. I’m not afraid of messy problems, and in fact, I seek them out. I completely geek out on opportunities to unpack and pull back layers of the onion to understand them and how different issues and problems collide to either make things better or worse, which is why the Financing Scale project makes sense to me.

What is one book that was meaningful or influential in your development as a leader?

Not as a leader, as a human – we are humans first. I pick up Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet the most. It’s so basic, straight forward and also beautifully written. I pick it up when I’m happy or sad. It’s got some extraordinarily direct and poignant life lessons in it that always tend to ground me.

Work in the social sector can be very personal and linked to one’s values. Can you think of a time when your values were in tension during your career and how you reconciled that tension or not?

I can’t think of time when my values were in tension per se, but I can think of more times – and maybe they’re the same thing – where I felt intellectual tension around the work. When you’re working with big systems and trying to change them which is work that I’ve done for many years, you sit across tables from lots of people who say they are about transformation. They are not, but you have to sit there. You sit there thinking how am I going to get this time back because this person is full of mess. I think we all have been in situations where we have to work with people who don’t share our values around change or supporting young people of color or don’t see the urgency of a problem the way that we might see it. That’s where I felt my strongest tension when I knew someone was just talking but wasn’t going to act and I had to sit there. I don’t know that you can reconcile that. I can’t make that person care about this issue the way that I care about it. It doesn’t matter what data I put in front of them. If their behavior has worked for them for 30 years there’s not much I can do to change them. Only thing I could reconcile was my reaction to it. I would play my own mental games in conversations like that to keep myself in control. I had to decide how much of me to let out in those kinds of discussions or interactions and would just imagine myself as a Tupperware container – letting out enough of me to let them know that I was serious without letting all of me out. Being measured was my way of reconciling those interactions which happened frequently, particularly working with big systems. I had to figure that out for myself and part of being a leader is knowing how to navigate those situations.

Summer 2017, Democratic Representative Maxine Waters coined the phrase, “reclaiming my time,” as she thwarted Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin’s attempts to waste her time with nonsense. Can you share an experience in the workplace where you have had to reclaim your time? What was the context? How did you navigate it? What was the outcome?

I would stick with the same example. How many times have I asked myself in meetings, “How am I going to get this time back?” Not how am I going to match this hour for hour, but all the energy being sucked from me in this stupid conversation that is supposed to be about children. For me it’s about how to get the energy back. I was fortunate to be working with young people because they would give me the energy back. Seeing them would remind me why I was doing the work and putting up with adults who didn’t get it.

What’s your approach to self-care? Are there any rituals you use to survive and thrive?

Cycling is definitely part of the answer. Self-care to me is a huge treasure chest and if you asked me this question while I was still at Philadelphia Academies, I may have answered differently. Self-care is about being able to design my work and my schedule in ways that allow me to learn things that I haven’t been able to learn before. I could have stayed at Philadelphia Academies forever. I loved the work, but at some point realized that things I needed and wanted to learn to stretch myself I could no longer learn from that position. Actually, I took time to develop a capacity and personal learning agenda. When I did mine there was a lot on it that I couldn’t do from that seat. I didn’t feel like I had a lot of new ideas for how to scale the work and scaling was what needed to happen. For me it wasn’t just self-care, but organizational care; they were connected.

When I transitioned, I knew what interests I had, but didn’t have a job. The other part of self-care became giving myself time and space – and I realize everybody cannot do this – to wander in the wilderness a little bit. I immersed myself in this Financing Scale project and joined friends at Sidecar. I have three rules in this new phase of me. 1) I will never again sit across the table from someone who says they are about transformation and they are not. It’s too much of an energy and intellectual suck. Again, I am 54 years old, so “no” to that. 2) Whatever I am doing next has to stretch me intellectually. 3) I am not walking fast anymore. That was a symbol of a hyper lifestyle I am trying to leave behind. I do fast on the bike.

Cycling is an anchor for me because it helps me stay fit. Also, since I’m doing it competitively it’s the only space where I put on my helmet and skin suit and get to use the ugliest stank eye ever towards my competition and it’s appropriate. It’s my badass gladiator space. I love the actual competition and it challenges me intellectually and physically. I’ve only been doing it for three years; there’s lots of strategy and technical aspects to the sport.

What advice would you offer other Black women trying to develop or amplify their voice and become self-advocates?

I have a 23-year-old daughter and am thinking about the ways I try to coach her. Sometimes we think that because we aren’t an “authority” that we can’t say or do certain things. You don’t have to be in authority to take the space. Sometimes we will get opportunities in our careers to take on bigger challenges but really every moment you’re at a table it’s a privilege and you have a responsibility to use your voice. To me, it’s not a choice. The choice is how you bring it, how you say it. What I tell Olivia is silence isn’t an option for you particularly in her instance where she’s the youngest and only person of color in her office. You can’t hold back because you’re too young or too brown or whatever; you need to put the issue forward even if scares you to put it forward.

In the context of my work, my husband was the mayor of Philadelphia for eight years. As First Lady, I had to get comfortable using those tables to put forth a voice that wouldn’t be heard otherwise. I think it’s hard if you’re “the only,” but you have to say it. It is tiring, though, so you have to pick your moments.

If you could change the social sector in a way that would benefit, lift up, or affirm Black women, what would that change be?

One of the things I have appreciated is seeing more women of color in philanthropy which means – it goes back to capital – greater influence in how money gets distributed. I worry most about and hope for us most is that we don’t get to a place of tokenism. “You want diversity? Black + women. Boom. All in one body!” (Laughter.)

I also worry about the fact that we may be asked to prioritize being a woman or being Black. What is first for you? It’s a tension for some Black women. Some think we are sometimes less threatening than Black men in these contexts, so I worry we could play into an easy route to inclusion. The advice I offer us is to make sure we are bringing others up and along with us. If we continue to be the only ones at the front door or at the table, then we are still the only ones and aren’t advancing the agenda. Intentional mentoring and sponsoring – which are two different things – vouching for others and bringing them along professionally. I’m saying that because, for me, I did have Black mentors in my life and some were not that intentional about my learning and development.

Comment section