Navigating Succession Planning

As I observe the growing list of open Executive Director positions in my daily newsletters; read the various versions of “stepping down” press releases; reflect on own my experiences entering and leaving leadership positions; and coach organizations through capacity challenges via the work we do at La Piana, it’s clear that succession planning still feels taboo to talk about, and our collective avoidance of the topic is keeping organizations from become stronger and more resilient, burning out leaders, and stifling future leaders from developing ownership and decision-making skills.

Broaching the Topic

I recently led a Learning Community titled “Proactive Planning for Leadership Transitions” as part of our BUILDing for Growth work with a cohort of the Ford Foundation’s grantees. The fact that we tied ourselves into a pretzel to avoid using the “S” word in the title was both an attempt to make clear that succession planning is something all senior leaders should plan for, and a desire to not scare away possible participants. Like creating a will, most executive directors, boards, and funders know it’s the responsible thing to do, yet because of its association with endings and loss, fears about an unknown future, and insecurities around feeling irrelevant or replaceable, we avoid it.

If you need to simply start the thought process, here are some potentially less-charged ways to think about succession:

“How can you celebrate and document the important work you’ve done?”

“What do you believe are the most important things for the organization to keep doing into the future?”

“What would you need to put into place to take a true extended vacation or sabbatical without worrying about being called for anything that might arise?”

“How can you best mentor the emerging leaders at your organization?”

And ultimately, “What do you want your legacy to be?”

Beyond the Actual Plan: Understanding Emotions (Yours and Others’)

The things you should do to plan for succession aren’t secret. Dozens of good tools and checklists are publicly available to guide your planning. Even a generative AI tool could probably write you a decent one. But even with the most ideal preparation, luxurious timeline, and level-headed planning process, succession planning can still go awry, because humans – with all our complicated feelings, motivations, and ambitions – can knock any well-devised plan off track.

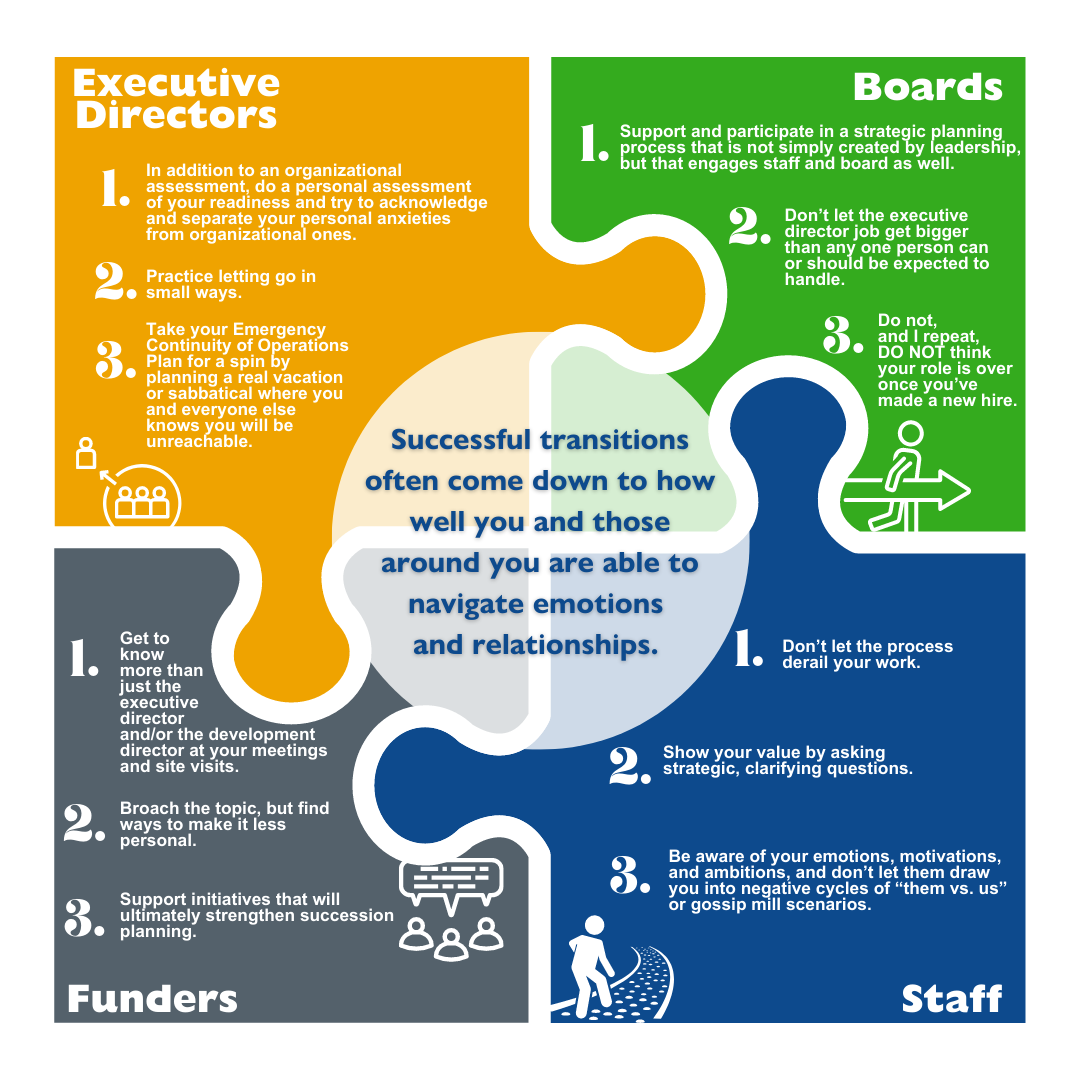

Successful transitions often come down to how well you and those around you are able to navigate emotions and relationships. Below are some important considerations for executive directors, boards, funders, and staff to keep in mind – they don’t apply to everyone or every organization, but they will help make you aware of common pitfalls. Regardless of your role, you can help make succession planning a smoother and more positive experience for your organization.

Executive Directors

Know that everyone is likely walking on eggshells around you. They are looking to you to gauge how they should be acting and embracing this change. You may say you are ready to leave, but if you are still tightly holding onto all decisions, you are giving a different signal. Let your vision about what’s next for you be your mantra to excite and motivate you to make a smooth transition. If you haven’t figured that out yet, try this tool. Here are three things you can do both to acknowledge your complicated feelings and to get used to the idea of leaving your organization one day:

- In addition to an organizational assessment, do a personal assessment of your readiness and try to acknowledge and separate your personal anxieties from organizational ones (financial, identity, purpose). Observe how you are talking about succession, and make sure your behaviors match your intentions. If you’re anxious or scared, that’s normal! Name it and help others around you support you through the process.

- Practice letting go in small ways. Audit your calendar and extract yourself from meetings you don’t need to be involved in. Ask others to begin making important decisions with you. Redirect to the appropriate person requests you’ve typically fielded out of efficiency or habit.

- Take your Emergency Continuity of Operations Plan for a spin by planning a real vacation or sabbatical where you and everyone else knows you will be unreachable. Don’t try to lay out every detail of what needs to be done and how to do it. Ensure clear decision-making parameters are set (how to make/who will make different decisions, and how to debrief and recalibrate). This will help everyone start building a leadership and accountability muscle. Rehearse broad scenarios rather than narrow cases. You may uncover some gaps that need addressing, but you may also be surprised. Either way, hopefully you’ll be refreshed from a well-deserved break!

Boards

Remember that hiring, evaluating, and planning for the succession of your Executive Director is your job. It will take time, resources, and will likely be exhausting. It may be the thing you most dread and so you avoid it – or think you can hire a search firm to handle it – but if you want to make it less painful for everyone, don’t slack until the time comes. The more you stay involved and engaged, the better you will understand the nuances of the organization and its culture, have good key working relationships that will smooth the process, and understand what key capabilities the organization needs in its future leader (hint: it might be different from those your current leader has). If you don’t have a point person or a team that has this on their radar, form one. Here are a few things you can do proactively:

- Support and participate in a strategic planning process that is not simply created by the executive director, but that engages staff and board as well – this broader participation will not only align and create buy-in to the organization’s priorities, but it will create a shared understanding of strategic thinking throughout.

- Understand what your executive director’s job is, make sure their expectations are aligned with the board’s strategic priorities, and ensure the organization is resourced to support the right size of staff for its work. Don’t let the executive director job get bigger than any one person can or should be expected to handle. This will burn out your current executive director and make it impossible to find someone who can or is willing to fill the role in the future.

- Do not, and I repeat, DO NOT think your role is over once you’ve made a new hire. Yes, it may have been a hard process, and this is supposed to be a volunteer role, but a new leader needs transition support in order to succeed.

Funders

Understand that, even in the most open and supportive partnerships you have with your grantees, they are still calibrating everything they say to you to make sure they make you happy. The fear of losing funding is always top of mind.

- Get to know more than just the executive director and/or the development director at your meetings and site visits. Make sure you’re cultivating relationships with other senior leaders and program staff, and engage them in conversation. Your appreciation for other leaders will positively enforce the idea that you support the whole organization and the mission, not just one person.

- Broach the topic, but find ways to make it less personal. Mandating a succession plan will not only feel patriarchal and trigger all kinds of worries (“does our funder think I need to step aside?”), but could also result in a “get it done to please you,” mentality. An organization that draws up a plan under these circumstances may end up creating a simple checklist instead of what you actually intended – an ongoing process of capacity-building and resiliency for the future. Consider hosting workshops for groups of grantees as a way to broach this subject, rather than an approach that is pointed at a specific individual or organization.

- Support initiatives that will ultimately strengthen succession planning such as: sabbaticals with interim executive support; fellowships for retiring leaders to undertake new purposeful projects and bridge financial worries; and strategic planning processes with leadership development goals.

Staff

It’s natural for you to worry about where you’ll stand with new leadership – whether you’ll gain or lose relative power and influence, if your responsibilities will change, or even if your position will be eliminated. Adding to that stress, you’re often left out of the process and, as a result, feel (and often are) powerless to have any input into decisions that will impact your life. Know that others are worried about how you’ll react too – if you’ll leave or quiet quit. Acknowledging the power dynamics at play, the more you can stay open, aware, and supportive of the process, the more you can learn about leadership, and position yourself as indispensable to the organization.

- Don’t let the process derail your work. Of course this is easier said than done. It’s distracting, and shifting responsibilities or reporting lines may legitimately be confusing, but the more you can keep current programs and operations running smoothly where you can, the better you can distract yourself from any drama. Focus on your mission-based work. You’ll also give leadership one less thing to worry about.

- Show your value by asking strategic, clarifying questions. Again, easier said than done given power dynamics, but by empathetically framing your questions, you can get the information you seek, and support leadership by offering insight into what staff are thinking (i.e., shed light on where there may be collective confusion, anxiety, or gaps in their considerations). By doing this, you can also help create shared understanding with your colleagues, and potentially influence how leadership interacts and communicates decisions with staff. “How should I be talking about this with clients?” “Can you clarify interim reporting lines and when they would end?” “If Suzie is now responsible for X, do we have a plan for ensuring that Y is being addressed while she has less capacity to focus on that?” “What role can I anticipate staff will play throughout this transition?”

- Be aware of your emotions, motivations, and ambitions, and don’t let them draw you into negative cycles of “them vs. us” or gossip mill scenarios. This feels good in the moment, but may ultimately be destructive for yourself and your organization.

Having a succession plan is about much more than creating a document. It’s ongoing discussion and process that can, if embraced, have many benefits to an organization beyond risk-mitigation. Undertaking this thoughtfully can refine decision-making and shared knowledge systems; increase transparency and build trust; provide everyone at the organization with a shared understanding of the “true costs of doing business,” and it can develop future leaders, creating resilience for the organization, and ultimately building capacity in the field.

This is an excellent and helpful approach to a difficult – and essential topic. I especially applaud the practical tips and tools for ED succession, and your framework for thinking about it across all the 4 big stakeholder groups.

Two additional important succession topics this makes me think about are –

Succession for key staff – Sometimes an organization relies deeply on one or few key staff who have become the holders of much of the ‘special sauce’ that enables the nonprofit organization to serve its clients in ways that make up the organization’s brand or comparative advantage, that is, those staff themselves make the org uniquely able to serve in its special way. If so, these positions too need a succession plan.

And secondly, board succession – Especially if the organization’s founder(s) comprise a prevailing force on the board, it’s critical for the board to be thinking ahead and planning to refresh and broaden the composition and longevity of the board itself.

Many of the concepts in this excellent blog post can be adapted from ED succession to key staff and board succession purposes as well – though additional thoughts and materials to support these additional succession planning topics (maybe as future posts?) would be most welcome!

Thanks again and congratulations on such a timely and helpful piece, Christine.

Beth

Your graphic is excellent. If I ever use it for a board retreat, I will certainly give you all the due credit. This is such an important part of the job. In my work with Boards, I’ve always tried to set them up with a sound process of term limits and recruitment processes that includes talking about the critical staff members such as ED. Everyone has a limit.

Thanks very much.

Courtney Johnson Philanthropy Advisors

Thanks, Courtney! And thanks for all the work you are doing to build capacity with Boards! Everyone, indeed, has a limit 🙂

~Christine